Nearly three years have passed since the 2021 murder of Chicago police officer Ella French, and police and prosecutors have revealed much about her killing: the grim details of her final moments, the type of gun used to shoot her during a traffic stop and how that .22-caliber Glock made its way into the hands of the man who pulled the trigger.

But absent from the public discussion was the name of the retail shop where the gun used to kill French was purchased. Its disclosure has been hindered by a long-standing push by the gun industry to protect the identities of retailers that have sold guns used in crimes.

The law enforcement agencies that investigated her murder and prosecuted her killer could not or would not say. Those that tracked and prosecuted the man who bought the gun used to kill her have been just as silent.

ProPublica, however, has learned the name of the retailer. It’s Deb’s Gun Shop, an Indiana retailer just over the Illinois state border that has drawn attention from federal regulators because of the large number of its guns that have turned up in crime investigations. James Vanzant, an attorney for the man convicted on federal charges for buying that gun, revealed that detail in an interview.

Speaking through his attorney, Deb’s Gun Shop owner Ed Estack called French’s death a horrible tragedy but declined further comment.

Credit:

Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Two decades ago, federal and local law enforcement routinely identified the source of guns used in crimes to members of the media or anyone else who inquired.

That changed in 2003 when Congress, bowing to pressure from the gun industry, approved legislation known as the Tiahrt amendment, named after a former Rep. Todd Tiahrt, R-Kan., a gun rights champion. The amendment bars police and the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from disclosing any information they uncover during gun-tracing investigations, including the names of retailers.

The move hobbled efforts by cities to study gun-trafficking patterns and ended what the gun industry has called a pattern of “name and shame,” in which retailers were thrust into the spotlight for selling guns later linked to crimes.

Gun safety advocates and researchers argue that Tiarht created a knowledge gap on a pressing public safety issue and allowed retailers to escape scrutiny. Such information, they say, can help the public determine whether the transactions that put guns in the hands of criminals are a rarity or part of a larger pattern.

The story of the gun used to kill French began in earnest in March 2021 at Deb’s, a small storefront off one of the main drags in Hammond, Indiana. Inside, Jamel Danzy picked out the Glock to purchase, then waited to pass his background check. On March 25, he returned and picked up the gun, prepared to deliver it to a friend.

He later admitted to ATF investigators that he’d bought the gun for Eric Morgan in violation of federal law. Danzy acknowledged that he knew Morgan was barred by federal law from buying a gun for himself due to a prior felony conviction. Morgan drove from Chicago to Danzy’s home in Hammond to pick it up.

Four months later, French, 29, was on night patrol in the West Englewood neighborhood when she joined other officers in conducting a traffic stop on a Honda SUV traveling with an expired registration. The officers inspected the car and found Morgan and his brother, Emonte Morgan, inside with a bottle of liquor.

The encounter escalated as officers ordered the brothers to exit the car, according to Chicago police. Eric Morgan jumped out and fled on foot. His brother stayed, refusing to put down his cup. A scuffle ensued. As French ran to help the other officers at the scene, Emonte Morgan pulled out the Glock and began to fire, police said.

French was struck and killed. Another officer, Carlos Yanez Jr., was severely wounded.

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Cook County prosecutors charged both Morgan brothers in French’s killing. Eric Morgan pleaded guilty to aggravated battery and unlawful use of a deadly weapon. In March, a Cook County court convicted Emonte Morgan of French’s murder. He has since petitioned for a new trial.

Danzy already was serving time by then. In 2022, he pleaded guilty to charges that he conspired with Morgan to buy the gun and lied by claiming on a required form that he was purchasing it for himself. A judge sentenced him to 30 months in federal prison.

The ATF, which investigated the purchase of the gun used to kill French, would not reveal the name of the Hammond retailer when contacted by ProPublica. Neither would federal prosecutors. In filings for the case against Danzy, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois did not reveal the name of the store where he purchased the Glock.

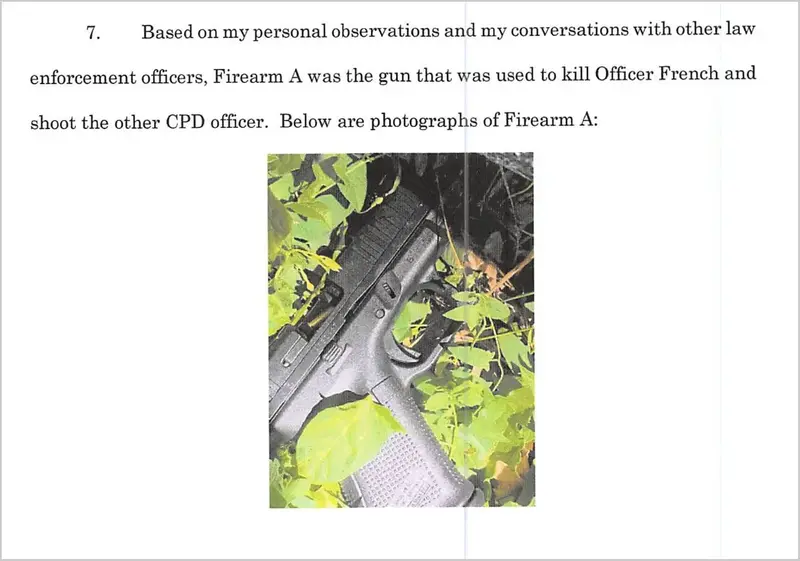

Credit:

Federal court record obtained by ProPublica

Tiahrt’s restrictions prevent investigators from disclosing the names of gun retailers, but federal prosecutors who try gun traffickers have more leeway. In fact, such disclosures in federal filings occur often.

ProPublica has viewed federal filings in both the Northern District of Illinois and the Northern District of Indiana where retailers were named in conjunction with cases against individuals who lied to make gun purchases or later resold the guns illegally in so-called straw sales.

One such gun was bought from an Indiana retailer and days later used in a shooting that left two Wisconsin police officers severely injured, ProPublica reported in March. The retailer involved was never charged yet still was named in court records.

Nonetheless, Joseph Fitzpatrick, a spokesperson for the US Attorney’s Office in Chicago, said it’s “our policy to not identify uncharged individuals or entities.”

As part of an ongoing lawsuit against the firearms industry, the city of Gary, Indiana, is seeking sales records from Deb’s and other retailers in the area. The suit aims to hold responsible local gun retailers and iconic gun manufacturers, such as Smith & Wesson and Glock, associated with illegal purchases like the one that led to French’s murder. The suit has survived court challenges for nearly a quarter of a century, but the Indiana General Assembly recently passed a law designed to get it dismissed. Deb’s is not a defendant in the suit.

ATF records show that Deb’s has operated under enhanced monitoring from the agency since at least 2021. The gun shop is included in a program known as Demand 2 for retailers who sell a high volume of guns later recovered in police investigations, according to records obtained by the Brady Center, a gun violence prevention group, and provided to ProPublica.

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Gun dealers can be placed in Demand 2 when ATF finds they are the source of at least 25 gun-trace requests from police in a given year; the retail sale of those guns must have been three or fewer years prior to that.

Besides the gun bought by Danzy, records show that at least one other firearm purchased illegally at Deb’s in recent years was central to a killing.

In 2021, Mark J. Halliburton shot and killed Monica J. Mills outside a school in East Chicago, Indiana, over a gun illegally purchased at Deb’s Gun Range. A prior criminal conviction prevented Halliburton from purchasing a gun legally, so he’d paid Mills $100 to buy the gun for him, according to court records. The two then argued over the deal one night inside a car in the parking lot of a school, leading to the shooting. The gun that fired the fatal shot was the same one purchased at Deb’s, according to police records. Halliburton later pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to 17 years in prison.

David Sigale, an attorney for Deb’s Gun Range owner Estack, declined to comment on Deb’s compliance record or associations with guns traced to crimes. “Deb’s continues to cooperate with all requests from law enforcement,” he said.

The ATF points out that involvement in the Demand 2 program does not mean a retailer has done anything wrong. Retailers’ location and the sheer volume of sales they process can make businesses susceptible to trafficking schemes, the agency told ProPublica in written answers. The program helps “raise awareness” among those retailers, ATF said.

Advocates for the gun industry say retailers in Demand 2 are operating within the law. “The illegal straw purchase of a firearm is a crime committed by the individual lying on the form. That is not a crime for which the firearm retailer is liable,” said Mark Oliva, spokesperson for the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a lobbying group for gun retailers and manufacturers.

Oliva also reiterated the group’s continued support of the basic tenets behind the Tiahrt amendment. “Access to gun-trace data should only be available to law enforcement taking part in a bona fide investigation, and law enforcement already has the access it needs for this purpose,” he said.

Kristina Mastropasqua, an ATF spokesperson, said Tiahrt helps protect the integrity of ongoing agency investigations and “does not negatively affect ATF’s ability to investigate and hold accountable illegal gun purchases or traffickers.”

But the debate over Tiahrt continues even as efforts to revisit it in Congress stall.

Dr. Garen Wintemute, director of the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California-Davis, said that Tiahrt’s restrictions have inhibited the study of illicit gun markets. He and others who study gun violence say they need the data to understand gun trafficking and, in turn, assess the regulatory efforts to prevent it.

“Firearms are associated with a number of adverse health effects,” he said. “Wouldn’t we like to know where that hazard is coming from?”

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

When researchers do obtain tracing data compiled by federal authorities, it’s usually under an agreement to keep the sources of the guns confidential. But there have been workarounds and exceptions. The city of Chicago and its police department facilitated University of Chicago studies that identified several Midwest retailers as the sources of thousands of guns trafficked into the city and then later submitted to the ATF for tracing.

The studies — published in 2014 and 2017 — link Westforth Sports, a now-closed Gary, Indiana, retailer, to 850 such guns recovered by police. There was no mention of Deb’s Gun Range in either of those reports. Shop owner Earl Westforth did not respond to a request for comment.

Other cities are continuing to look for ways to navigate around the Tiahrt amendment. The city of Baltimore, for instance, is suing the ATF over its denial of trace data.

That drew the ire of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which moved to intervene in the case. “This is a transparent attempt by gun control advocates at the City of Baltimore … to gain access to the data to use it to smear licensed firearm retailers and manufacturers by suggesting they are responsible for crimes committed by others misusing lawfully sold firearms,” foundation Senior Vice President Lawrence G. Keane said in a statement.

In arguing for the gun-trace information to stay under wraps, foundation attorneys cited federal law — specifically the Tiahrt amendment.